But For One Number, There Go I

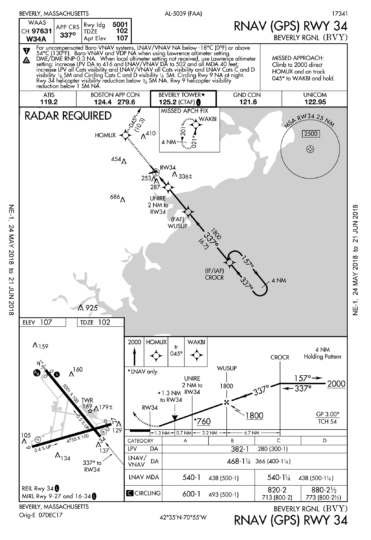

Sometimes, it starts with a simple question. This time it concerned the RNAV (GPS) Rwy 34 approach at Beverly, MA (KBVY). The query was, “Why is radar required?” The answer isn’t as obvious as you might think.

“Radar Required” appears in the plan view when there’s no way to navigate from the enroute structure (a.k.a., airways) to the initial approach fix (IAF) without the help of a kindly controller. The most common reason for this is that the approach has no IAF. Such approaches require ATC vectors to the intermediate fix (IF) or onto the final approach course.

That’s not true here. CROCR serves as both IAF and IF. You can cross CROCR from any direction, fly a hold-in-lieu-of-procedure-turn (HILPT), if needed, and head inbound. (As an aside, I want to fly this approach just to check in with Tower at the FAF of WUSUP by saying, “Beverly Tower, Cirrus One Two Thee Alpha Mike, RNAV Runway 34—Wuzzup?!”)

Sometimes, radar is required because the IAF, or a fix that starts a feeder route to the IAF, isn’t depicted on the enroute chart. The FAA assumes we need a certain amount of “connect the dots” assistance matching a fix on one chart to the same fix on the next chart we use. That restriction doesn’t apply to RNAV waypoints, however, so that’s not the reason for “Radar Required.”

In fact, that’s what’s so odd about any RNAV approach requiring radar. You must have RNAV to fly this approach, so you must be capable of flying direct CROCR from any nearby airway. You could fly direct CROCR from Kalamazoo, if you wanted. Why do you need ATC radar?

Heading and Altitude

The only thing missing in a formula for flying direct CROCR is altitude—and that’s the reason for the note, “Radar Required.” There’s no Terminal Arrival Area (TAA) for this RNAV approach. There are no feeder routes to CROCR. Therefore, ATC must see your position on radar to assign the altitude to maintain until CROCR.

There is a Minimum Safe Altitude (MSA) on the chart. In case you’ve forgotten, the MSA covers a radius from some fix on the approach and is an obstruction-free altitude. In this case, it’s a 25 NM radius from the missed approach point of Runway 34, as specified by the text “MSA RW34 25 NM” curving around the MSA circle.

MSAs are for emergency reference only. It’s for when everything goes to hell, you’re off course, and just need to get to a safe altitude to regroup. MSAs don’t even apply to lost communication unless they’re higher than your last assigned altitude and you’re flying off-route within the MSA radius. If you were direct Beverly and told to expect this approach, and then you lost communication, you’d maintain your last assigned altitude until crossing Beverly Airport, maintain that altitude to CROCR, and only then descend in the HILPT to commence the approach.

For RNAV approaches with TAAs, no MSA is published. It would be superfluous. The TAA sectors you would normally use to transition onto the approach, double as safe altitudes you can use in an emergency. Why some RNAV approaches get TAAs and others don’t is known only inside the back rooms in Oke City. Maybe, in this case, it’s the proximity of Boston. It’s certainly not due to obstacles; that grey area is the Atlantic Ocean.

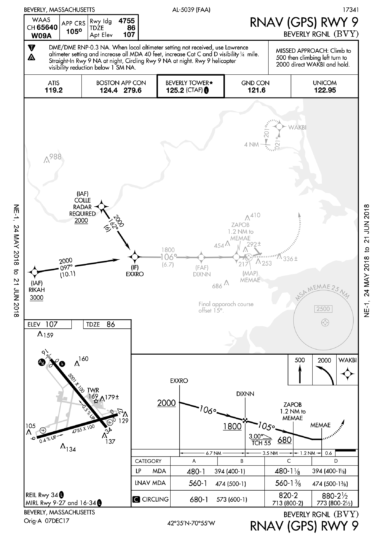

This discussion gets more interesting when you look at the RNAV (GPS) Rwy 9 approach. This approach has two IAFs, one at COLLE and another at RIKAH. COLLE shows Radar Required, and a minimum crossing altitude of 2000 feet. The latter is odd because if radar is required, you’d only arrive at COLLE on a vector or direct-to from ATC. That would include an altitude to maintain. The segment from COLLE to EXXRO is also 2000 feet, so you wouldn’t descend after COLLE. I don’t have a good answer why this restriction is shown.

RIKAH is a different matter. There is no requirement for radar—even though this is an RNAV fix unattached to an airway, like COLLE. The 3000-foot crossing restriction here makes sense because, without a radar requirement, you might be choosing your own attitudes, and the segment from RIKAH to EXXRO has an MEA of 2000 feet. You must cross RIKAH at or above 3000 feet, and can only descend after crossing.

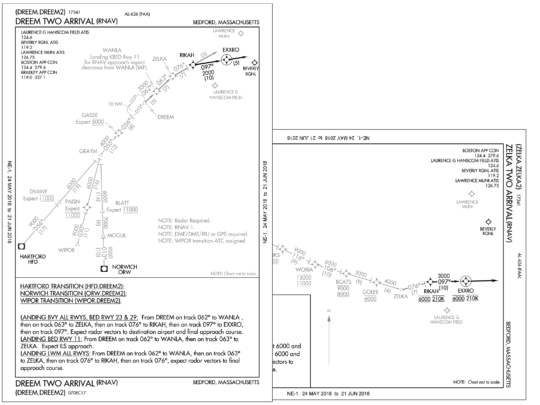

To see what’s special about RIKAH such that it doesn’t require radar takes some more chart hopping. The reveal happens when you review the DREEM TWO and ZELKA TWO arrivals. RIKAH is depicted on both these charts. This provides a path from the enroute structure complete with MEAs for each segment.

A pilot could fly a complete route from enroute through arrival to approach without any information required from ATC. That’s presuming said pilot did all the document searching to figure out how the dots connected. The takeaway from this is our IFR system is truly an integrated system. Individual pieces, such as an approach chart, might make no sense out of context.

It also might be entirely academic. If I were expecting the DREEM TWO and went lost comm (or a failure of ATC radar meant the other approaches at Beverly were not available) I’m not sure I’d accept the RNAV (GPS) Rwy 9. I might invoke emergency authority and MSA my way over to a more favorable approach. I might do that in the daytime; I’d absolutely do it at night. Watch the video to see why.

Or I’d simply go elsewhere. There are times the lack of official blessing on one little number breaks the system.

Watch This Video:

Straight-in and Circling NA at Night

Fly-over versus Fly-by

While we’re discussing academic points, there’s a symbol on the DREEM TWO and ZELKA TWO that appears on many approach charts, but is so small it’s easily overlooked. The standard waypoint symbol is a four-pointed star. These waypoints are fly-by waypoints. EXXRO shows this symbol circumscribed by a circle. That makes it a fly-over waypoint. Most missed approach points on RNAV approaches are also fly-over waypoints.

There’s a misconception that “fly-by” is synonymous with “Eh, close enough.” So long as you pass within a mile or so, you’re good. While it’s true you don’t need to cross directly over a fly-by waypoint, that’s not the real point. You’re bound by FAR to fly the center of a route no matter how you’re navigating it. That includes fly-by waypoints.

The reason fly-by waypoints exist is that when a route bends, it’s acceptable for your navigator to anticipate the turn and guide you in an arc that leaves the segment directly to the waypoint and smoothly joins the next segment departing the waypoint. Obstacle clearance is based on an assumption you will make this early turn, rather than the old-school overflight of a VOR before turning to join the next leg.

If that early turn can’t be accommodated or simply isn’t permitted, the waypoint is depicted as fly-over.

ForeFlight Question of the Month

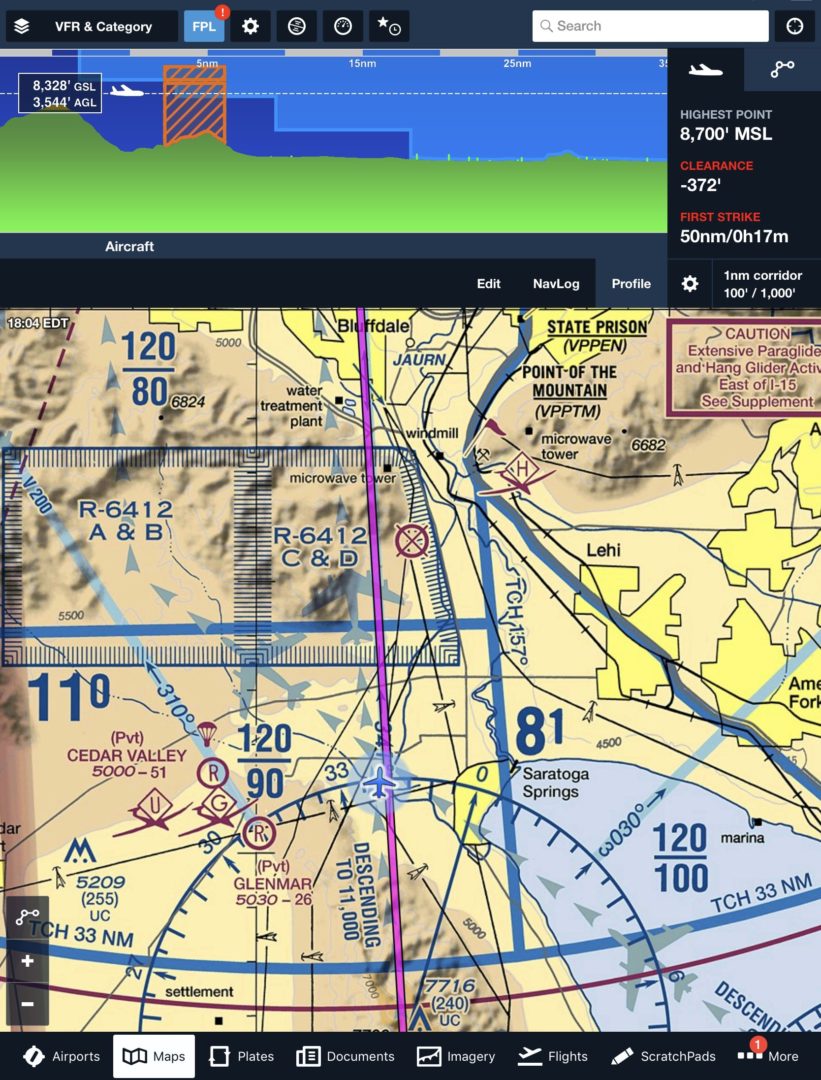

Click here to view larger image

You’re flying along VFR and note both restricted airspace and Class B airspace ahead of you. (Must be your lucky day.) Presuming you have a ForeFlight subscription with a profile view, if you tap the airspace ahead in the profile, what information will you see?

A. You’ll see the upper and lower limits in the Profile View only.

B. You’ll see the upper and lower limits in the Profile View, and the lateral limits in the Map View.

C. You’ll see the upper and lower limits in the Profile View, and the lateral limits in the Map View with the map zoomed to show just that airspace.

D. Tapping the airspace in the Profile View shows nothing. You must tap in the Map View.