Better Practice Approaches

It’s easy to get in a rut practicing approaches around your home ‘drome. You know the airports; you know the frequencies; you fly with the same buddy before stopping at the same airport diner for the same pastrami on rye.

Or, maybe you don’t even practice approaches enough to have a “same.” Don’t feel bad; you’re not alone.

The winter months see more IFR practice than travel for many light GA pilots. So, amp up your practice—and make it more appealing to do on a regular basis. (Set aside the simulator discussion for now. Let’s just talk about real-world aircraft.)

The two best things you can do are making practice a habit and upping the stakes. The first part is pretty simple: Set a recurring day, say the second Saturday of each month, when you and a friend or two go bore holes in the IFR system for practice. Three people are better because two get to watch while one flies, and there’s still a party if one of the gang must take a day off.

Upping the ante on the experience can happen in many ways. Here are a few suggestions:

* Have a focus. Each time you fly, have one thing that’s the core practice for the day. Maybe today it’s partial-panel approaches with an ILS or LPV. That’s all you do. You get to focus on exactly that skill and dial it in. Stick with items that make sense in the real world. If you were really partial-panel, you’d almost certainly find an ILS or LPV, so practicing partial panel without vertical guidance isn’t realistic—unless when you lose your PFD you have no vertical guidance. In that case, partial panel and non-precision would be a great thing to practice.

* Request the option. Rather than ending every flight with a missed approach, let your safety pilot make the call just as you reach minimums or a reasonable visual descent point. You’ll be ready for either. Also, having an option to land might force you to fly a more difficult approach for the runway in use, or fly to circling minimums and circle to the landing runway. Circling is a great skill even if you’d only use it with high ceilings and in daylight. Circle no lower than pattern altitude if you want, but practice maneuvering to land somewhere other than straight-in.

* Remove one thing. This could be a focus topic or something your safety pilot tosses in at random. Just lose one of the tools at your disposal and see what it does to your process. It could be the iPad, your second radio, electric trim, the MFD, flaps, etc. Remove just one thing, however. A variant on this is losing one part of the approach system at the last minute: no glideslope, no GPS position, only an approach with a tailwind available. The key is you don’t know what, or when, until it happens. Your flying buddy(ies) get to surprise you with that one.

* Place a bet. Want to really make practice count? Rate the approaches and have the loser buy lunch. Or the avgas. Believe me, you’ll try harder. The safety pilot must watch for traffic, but if he also has an iPad or tablet, have him grab screenshots for proof. Ideally, the screenshot would show speed and altitude as well as position. ForeFlight, CloudAhoy, or Flysto recordings are great tools for this.

* Debrief. I’m as guilty of not debriefing my own practice as anyone else, even though the instructor in me knows the debrief is as important as the flight itself. Take notes on the other pilot’s flight and have that pilot take notes for you. Use those screenshots as you discuss what happened while you enjoy that lunch. Or beer if the airplane is tied down for the night.

The pilot flying does all the communicating with ATC, except for special requests and traffic calls. A good safety pilot can think ahead and ask for things like alternate missed approach instructions that get you going in the best direction for the next approach … or ask ATC for an impromptu hold to let you catch your breath if things start to fall apart.

Having the right safety pilot is key. You want someone who’s not only legal but knows your airplane and your avionics well enough to give feedback on how you did. If you’re swapping approaches, knowing the equipment is required. It’s helpful to have the safety pilot plan ahead for your next approach request. You also want someone you get along with—and won’t gloat too much when you have to pick up the tab.

Watch This Video:

Practice Approaches and Downgrading GPS Quality

Practice in VFR Conditions

Practice approaches in clear air are the common fare, and the only option in the icing months. This means you can practice without even filing IFR—which is a real boon if your currency has expired. However, VFR practice puts you into a nebulous region where you get some of the ATC services, but not all of them.

The big divide concerns separation services. When these services are provided, you’ll get an altitude to maintain when on an ATC vector. Clearance for the approach means you’re still getting separation from IFR aircraft. When not restricted by ATC, altitude is your discretion. That can confuse pilots when they’re direct to a fix, expecting to get a lower altitude and it never comes. If in doubt, just ask.

When there are no separation services, altitude is entirely your discretion. In this case, you’ll usually hear, “Maintain VFR. Practice approach approved. No separation services provided.”

Also, keep track of airspace. Talking to ATC for VFR practice approaches meets the requirement for entering Class C airspace, but not Class B or Special Use Airspace. Don’t count on ATC to steer you clear of it.

Reader Question

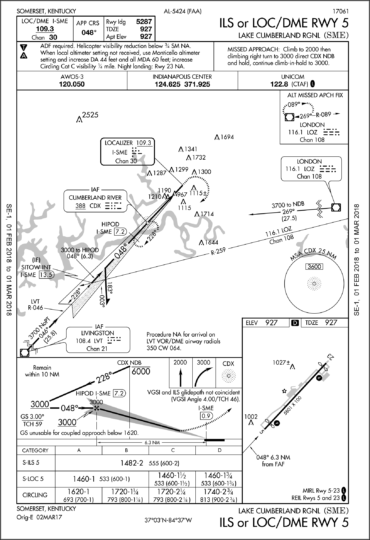

“Why would the ILS minimums be higher than the LOC minimums on this approach? Thanks! Jon.”

Click here to view larger image.

Jeff’s Answer:

It’s impossible to know for certain without seeing the documentation for the approach, but an obstacle close to the airport is the most likely reason. Possibly it’s that tower shown just off the approach end of the runway. I know it seems odd that you’d have to start an ILS missed approach higher than the Localizer-only MDA, but there are two things to consider:

- The ILS has a DA, which is the point where you decide to go missed, but the aircraft will take time and distance to change from a descent to a climb. This must be accounted for. A DA of 1482 feet means the aircraft will descend below 1482 feet as it initiates the missed approach. Less power-to-weight and longer spool up time for the engines means a lower descent below DA before climbing again. It’s not uncommon for heavy commercial aircraft with Cat-II, or -III DAs close to the runway to actually touch down momentarily during a missed approach from minimums.

- The shape of the protected airspace is different for ILS versus localizer approaches. It’s possible for an obstacle in just the right spot to affect the ILS approach but not the localizer approach.

Tech Question of the Month:

Click here to view larger image

Can you get ForeFlight to work with your desktop flight simulator?

A. Yep. Every feature of ForeFlight can be driven by home simulation.

B. Sort of. You can use real-world weather for both sim and iPad, and receive the GPS position and attitude information from the sim on ForeFlight.

C. A bit. You can receive the GPS position, but that’s it.

D. Not without special hardware. There are cables you can buy, but nothing simple and free.