Making Avionics Sing

I’m an unabashed geek when it comes to avionics. My flight instruction career has lived in parallel to one in technical education and writing. It also started less than a year after Garmin introduced the original GNS 430, so maybe it was destiny that my niche would be avionics training and IFR training.

That said, I despise pushing pixels around just for the wow factor. I want every bit of tech to do something for me. The effort needs to have some payoff in speed, ease, or safety.

Obvious payoffs are simple, but subtle ones can be equally important. How you use your cockpit technology affects how you interact with the flight. It reinforces—or erodes—habits that promote safety. Put more grandly, the way you use your cockpit tech changes the way you think in flight.

Here’s a simple example: My GPS navigator is always set up to show the desired track (DTK), actual track (TRK), and cross-track error (XTE). From takeoff, through en route, and on approach, I’m checking and correcting to keep DTK and TRK equal. My game is to keep XTE, which is my lateral distance off-course, to under 0.05 miles. Ideally, I’ll keep it under 0.02. That’s 180 feet left or right of course.

ATC can’t see that level of deviation. The en route CDI is centered even if you squint. In fact, there’s no compelling reason to fly that precisely except on approach. Even then, 180 feet left or right will pass an ATP exam with room to spare.

However, maintaining that pervasive awareness of desired track and heading keeps me engaged in the flight in a way I wouldn’t otherwise be. Small changes in winds are immediately apparent. That, in turn, makes me consider the validity of the forecast, check my groundspeed, review my fuel at the destination, consider which off-route airports are downwind from me, should I need one. It even tunes my scan and awareness of trim: “Why do I keep rolling a bit left today?”

All of that is fallout from one screen customization and habit.

Of course, I’m human and easily distracted, so I’ll look over at times and see an appalling XTE of 0.4. Aviation is terrific for promoting humility. The point is that these little tech habits add up. There are dozens, so here are a few more of my favorites.

Terrain on a secondary map: This started when flying G1000 systems where I could put terrain awareness on the moving map. The problem was that the entire MFD becoming yellow, then red approaching an airport didn’t sit so well with passengers. It was better to show terrain only on the little PFD inset map. That way, only I could always see the location of high terrain around the airport on approach. With dual GPS navigators showing terrain, I prefer to have the secondary navigator show terrain on the approach.

Loading destination frequencies from the database: It’s simple to dial in your destination frequencies after reading them from the approach chart. However, your GPS has those frequencies in its database as well. I like to load them from the waypoint pages specifically to stay facile with using those waypoint pages. If my tablet dies in flight, or just slips out of reach, grabbing frequencies or other data from the GPS is a ready skill. I also find it just improves the mindset, “OK, time to really review and set up for my destination.”

Monitoring airports below or Guard: I’m a big fan of listening to airports I’m over flying when it’s VMC and I’m not very high. More than once, I’ve heard traffic that could be a concern before ATC called it. It also keeps me in tune with what’s going on in the aerial world around me. My favorite way to do this is using the monitor function available on some radios (including the GTN 650/750, SL30, and GX60). Monitor auditions both the active and standby frequency of the same radio transmissions on the active frequency mute the standby one. Up high or IFR, I can tune Guard in standby and monitor it. Of course, monitoring can be done with two radios as well, but without the auto-mute.

Weight and balance, and performance planning on the tablet: It’s easy to gloss over this planning because our aircraft performance is well within the requirements for most of the airports we use. However, knowing roughly where you should rotate is a great check for any subtle issues affecting your craft. Knowing your landing weight is the first step in determining a correct reference speed for landing. Many GA pilots, without an AOA indicator, use the same final approach speed regardless of weight. Yet for any airplane with a short-final speed over 70 knots or with a useful load pushing 40 percent of gross weight, adjusting landing speed for weight will improve landing quality and control. It also promotes determining and holding a precise speed on approach (presuming that’s appropriate procedure for the landing you have in mind).

Nearest airport on the tablet: Back in the days of flying needles VOR to VOR, an emergency diversion to an off-route airport was by ATC vector or best guess using your thumbs on a paper chart. The moment we had direct-to, magenta lines, and the nearest page on a GPS, it was a self-navigating snap. The irony is that with a moving map, particularly on a tablet, it’s never been easier to play “what-if” games measuring distances and directions to airports if you must make an emergency diversion. Just the act of doing that keeps you more aware of your surrounds and your position along the magenta line as you fly.

And that’s really the takeaway here: You can use the tech to compensate for disengagement or to promote active engagement. It’s your call, but active engagement is undoubtedly safer. And speaking from my own experience, it’s simply more fun.

Watch This Video:

“Three Handy Garmin GTN 650 Tricks.”

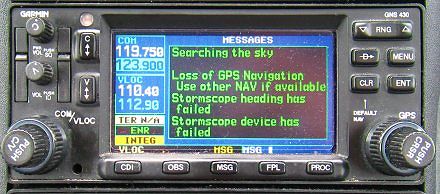

Practicing Single-Box Failures

The flip side of squeezing maximum utility from every box is the ability to deal with that box failing at the most inopportune time. If you fly with two nav/coms, you probably use one as your primary and one as your secondary. Fly a series practice approaches with the primary nav/com powered down. Even if you don’t lose specific capability, such as GPS approaches, just the disruption to your normal flow can throw you off. Also, your MFD, traffic display, or other cockpit devices might not work with the GPS inoperative. Try tossing your tablet in the backseat and finishing the flight using your backup device, which might be just your smartphone.

You can take this as far as you want, such as flying the entire approach with the pitch trim still in the cruise position if you only have electric trim. The point is failing a single system and playing out all the repercussions, both obvious and subtle.

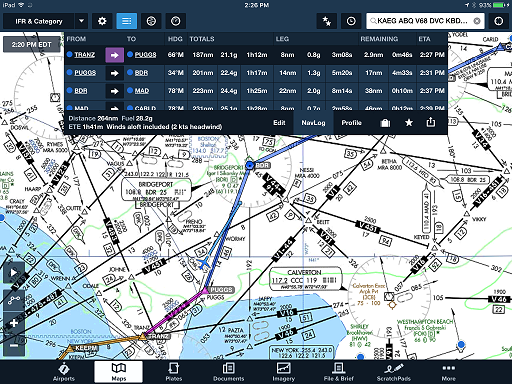

ForeFlight Question of the Month:

You’ve been vectored off your route and are now given a heading to rejoin it, rather than direct to a fix along the route. On your GNS 430W, that’s done by activating a leg and flying onto it. How can you activate a leg in ForeFlight?

A. Tap the next waypoint, then tap and hold the direct-to icon. When the pop-up appears, select a direct-to course matching the leg you want to intercept.

B. Tap and hold the waypoint at the end of the leg to activate and select “fly leg” from the pop-up.

C. Tap and hold the waypoint at the beginning of the leg to activate and select “fly leg” from the pop.

D. In the Nav Log, tap between the waypoints defining the leg and select “fly leg” from the pop-up.

E. This can’t be done in ForeFlight.