Visual Approaches

One of the great ironies of IFR flying is that once you have the right to fly through the clouds, you take almost every opportunity to stay out of them. It’s simpler, faster, and arguably safer (at least at the GA level) to shortcut full procedures with visual ones. The go-to “instrument approach” for keeping the mail moving is: “Cleared for the visual.”

However, a casual demeanor can be an invitation for catastrophe — or at least a letter of investigation from the authorities. So it’s worth a review of the corner-cases and gotchas hidden in the plain-sight (visual) approach.

First off, conditions must be basically VFR. Weather reporting at the destination isn’t required so long as some reliable source says there’s at least 1000-foot ceilings and three miles visibly. In practice, it often requires more. The pilot can ask for the visual, or ATC can assign it. However, the pilot must have the airport, or the preceding aircraft, in sight.

There’s trap number one: When you report the preceding aircraft in sight, you are responsible for separation. If you lose track of that aircraft (or the airport), you must tell ATC ASAP. If you’re at an uncontrolled airport, that may mean switching frequencies back and asking ATC if they still see that aircraft on radar.

On those lines, once ATC clears you to contact Tower or the advisory frequency, radar service is automatically terminated. Don’t be fooled because you still have a transponder code. You’re still IFR, but you’ve assumed separation from both aircraft and obstacles. This is true if you ask to switch to advisory early as well. It’s unlikely to be an issue while the sun shines, but when you’re cleared for the visual at night, that’s another story. Sometimes it’s a story of a Southwest 737 that lands at the wrong airport because ATC was no longer watching with the God’s-eye view.

That said, ATC can’t release you unless all traffic conflicts are resolved. Given that there’s no restriction on how you proceed visually to the airport, sometimes you’ll get cleared with a restriction, “Maintain 4000 and contact Tower …” or something similar. Take that as a heads up there’s a potential conflict that needs tying up. At bigger airports (pretty much Class C and above) there are complex letters of agreement on exactly where and how Approach can release visual approaches to Tower to minimize issues. RNAV aircraft can be cleared direct to a published FAF as part of getting cleared for a visual.

Technically, ATC could release two aircraft on visuals to the same uncontrolled airport provided the second one had the first in sight. In practice, that’s the kind of scenario that gives controllers hives. Two aircraft, out of communication, both going for the same airport, yet both IFR with requirements to protect the airspace in case they pop back up needing services again.

A takeaway for us pilots is that when cleared for a visual to an uncontrolled field, we tie up that airport — and maybe other nearby airports — until we cancel IFR. That may seem bizarre on a CAVU day when the pattern could be full of VFR aircraft, but it’s true. So if you can cancel, do it. If you can’t contact ATC directly, try relaying through that aircraft behind you. And if you’re the aircraft behind waiting for the visual, call to the person in front and see if they’re willing to cancel, or just cancel yourself and proceed VFR.

There’s not much gain in retaining your IFR status if you can cancel and fly VFR. You must maintain VFR cloud clearances appropriate for the airspace. That’s likely the common 1000 above, 500 below and 2000 feet laterally, potentially all the way to the surface (see sidebar: Over-Eager IFR Cancellation).

The only real gain in staying IFR is if you can’t land. There is no missed approach procedure for a visual. You’re expected to land as soon as practical if you go around, or stay clear of clouds until issued a new clearance. But that should come faster if ATC still has you in the system. And there won’t be any other IFR aircraft in your way.

Another point is that when you’re cleared for a visual to a towered airport, it’ll often be a visual to a specific runway. That’s a clearance, and changing runways requires permission. A visual to an uncontrolled field won’t have a runway assignment, but you’re still bound by the local traffic patterns. If it’s right traffic for Runway 36 and you’re arriving from the west, you’re expected to cross over the field before entering the downwind. It should go without saying that you’ll monitor the CTAF as early as possible and fit yourself into the VFR traffic flow as politely as practical.

Controllers need at least 500 feet cloud clearance above the MVA to vector an aircraft on a visual. There are workarounds. A controller can drive someone on a downwind for a published approach — that’s not a vector for a visual — but know they’ll likely report the field in sight and can hop off on a visual. Remember, if you’re cleared for a published approach, you can’t spontaneously switch to a visual. But you can always report the airport in sight and ask.

Lastly, keep the visual approach clear in your mind from its sister tool, the contact approach. The key difference is that the visual is essentially a way to complete your flight in VFR conditions and with VFR simplicity. The contact approach is akin to Special VFR. The requirements are only one-mile visibility and maintaining clear of clouds. You don’t need the airport in sight, so long as you have reasonable confidence in getting there visually. It can’t be assigned; the pilot must request it.

Personally, I prefer requesting a contact approach rather than a visual when I’m making the request because I get all the flexibility without a requirement for the airport to report VFR conditions.

Well, almost all the flexibility. You can’t ask for a contact approach to an airport that has no published approach procedure. You can do that with a visual. Similarly, you can’t fly part of a published approach to Airport A and then sidestep on a contact approach to Airport B. That’s a common request with a visual.

And well it should be because that’s how the mail keeps moving … so long as the conditions are right.

Watch This Video:

“Special VFR vs. Contact Approach.”

Over-Eager IFR Cancellation

You can almost hear the longing in the controller’s voice: “Report IFR cancellation on this frequency or (sigh) on the ground …” If you can safely and legally cancel IFR before landing at an uncontrolled field, it helps everyone in the system. Safe is up to you, and often not an issue. Legal? That can be a gotcha.

Remember that you must be in VFR conditions appropriate for the airspace because you forfeit all IFR privileges when you cancel. That’s easy to forget with runway lights in sight after two hours of droning along in IMC. The classic trap is when the airport has a Class E surface area, so the rule of 2000 feet laterally and 500 below extends all the way to the surface. As much as you might want to cancel IFR in the air so the next aircraft can get in behind you, it’s a violation of 91.155 if you can’t maintain VFR, or the ceiling is less than 1000 AGL. It’s worth noting where those Class E extensions are for approaches, and what happens at towered airports when the tower closes. Some revert to Class E at the surface. Others become Class G.

Cancelling early isn’t a big-time savings to you, especially if there’s radio reception or cell phone coverage on the ground. Call the clearance delivery number at 888-766-8267 to cancel. Or even relay your cancellation through the waiting aircraft.

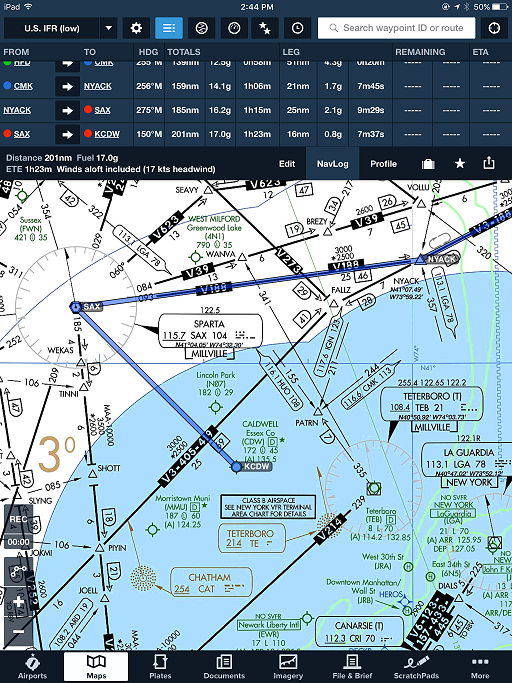

ForeFlight Question of the Month:

You’re setting up for an instrument approach to your destination and want to add the waypoints of the approach, including the transition, to your flight plan. You do this by:

A. Adding them from the plates tab that displays the approach plate.

B. Adding them using the procedure function in the nav log editor.

C. Showing the plate on the map, and then adding them from the pop-up plate menu.

D. Showing the plate on the map and adding them manually. There is no automatic way.