Don’t Disable. Revert!

They say automation breeds bad habits, but I think automation training is where the blame lies.

Here’s one beef: What should you do when the autopilot fails to capture the glideslope or turns right when you expected left?

You should disengage the autopilot and hand-fly, right?

Wrong. Wrong. Wrong.

Think about this objectively for a moment. Right at a critical moment in the approach, you’ve been hit with a surprise, so you immediately throw out one of your best IFR tools and double your workload. You do it right when a precise flying action is required. And you’re distracted because part of your attention is off thinking, “Why did the autopilot do that?”

But Disengaging is Easier

Yes, disengaging the autopilot is the “easiest” way to fix the situation, and that’s the problem.

It’s easier because we rarely do what I’ll call “Reversion Training.”

With one exception (which we’ll talk about in a moment), I have yet to see an autopilot surprise anybody in heading and basic altitude mode. If it does, the thing is probably broken, and then we’re in agreement it should be turned off. The reason is simply that heading mode and simple altitude or vertical speed hold are direct commands for performance. Fly left. Go down. Stay here.

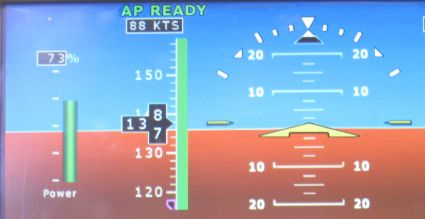

This means that even in a critical moment, using these simplified functions should be an easy way to command your aircraft without abandoning the autopilot assistance altogether. When the more complex navigation or approach modes let you down (usually because something was entered incorrectly or too late), revert to the simpler heading and altitude modes and put the airplane where you want it. You know where the aircraft should go, or you wouldn’t be complaining the autopilot is misbehaving.

Building this habit of reverting down one level of automation takes a little practice. We have to break the red-button-disconnect habit, and we must build some skill using heading mode for more than vectors.

Step one is probably changing how you engage your autopilot. Do you go straight from hand flying to NAV mode where George follows the pretty magenta line? Don’t.

Instead, start with a Roll-and-Pitch hold mode if you have it. Essentially that’s the simplest autopilot mode of all and it’s easy to see if it’s working. When you engage roll and pitch holds and release the yoke, nothing should change.

The next step up is Heading Mode with a selected Vertical Speed or Altitude Hold (or just trim if you have only one axis of AP control). How’s that working? Great. Now you can take the last step up to advanced navigation modes.

Making a practice of stepping up lays the foundation for stepping back down when you need to. Part two is practicing entire approaches using just the heading bug and basic vertical speed control. It’s not hard. In fact, it’s kind of fun, but it takes some practice. You should be completely comfortable flying both ILS and LPV approaches with a continuous descent and non-precision approaches with level-offs and power changes using HDG, VS and/or ALT, and the throttle(s). Yes, you must also be comfortable hand flying approaches in case the autopilot completely fails, but that’s a different article.

There’s one other habit that’s useful for many reasons, but essential here. Make a habit of syncing your heading bug to your current heading on a regular basis, even if the bug isn’t in use.

The one time reverting catches people off guard is when they engage the autopilot HDG mode without realizing the heading bug is 110 degrees to the left. The aircraft dutifully rolls off toward the bug as the pilot makes a mad scramble to the swing the bug back forward.

To successfully and smoothly revert, you must have these details covered. Master that, and a misbehaving autopilot is almost boring.

Watch This Video:

“How to Fly a Flight Director”

Hand-Flying the Easy Parts

The simple fact is you get good at hand-flying an aircraft by … hand-flying an aircraft.

Something you notice watching many pilots fly is that few have trouble hand-flying when they’re focused on the gauges. The actual motor skill is not the weak part. The weakness is in split attention.

Out-of-practice pilots get into trouble because they’ve lost the skill of maintaining a pervasive and constant awareness of the flight instruments while they do other tasks.

Here’s a good exercise for that: Don’t use the autopilot in cruise. Use it for climbs or descents as you get ready for approaches if you want. Use it for at least some approaches as well. But when things get boring, turn it off. Your mind will naturally wander—forcing you to practice continually checking back to the flight instruments. Regularly reinforce hand-flying skill when life is relaxed, and it’ll be there for you when things get busy.

ForeFlight Question of the Month:

You bring your Stratus 2 along to fly with a friend in her tailwheel Cessna 180. You place it on the glare shield during startup and it seems to work fine, but when you level out, the attitude display (HUD) shows 10 degrees nose down.

You realize this is because the glareshield in the 180 is angled to be level with the tailwheel down, so it’s sloped quite downward in flight.

The simplest way to deal with a pitch up, down or otherwise misaligned HUD in Foreflight is:

A. Resetting the level point for the Status in-flight from the

device settings.

B. Resetting the level point for the Stratus in-flight from the

AHRS button on the HUD.

C. Holding the Stratus at just the right angle when it first starts

up on the ground.

D. Restarting the Stratus in flight view.