Welcome to Practical IFR

Practical IFR (PIFR) is a cross between a blog and an in-depth article. Content-wise it’s serious IFR, delving into a specific IFR topic from a pilot’s perspective. Each installment of PIFR offers practical tips and techniques for getting the most utility out of your IFR flying.

Do you turn onto the localizer if you’re about to blast through it but haven’t been cleared? If you’re gliding engine-out in IMC into a headwind, what speed should you fly? Why can lowering your personal minimums make you a safer pilot? These are the questions PIFR takes on.

In addition to the core article, there will often be a video digging deeper into a related topic. These usually focus on specific tips for getting the most from your avionics. There’s also a monthly quiz question and answer on using technology, which is as much a part of modern IFR as bulky approach-chart binders were back in the day.

Would You Intercept the Inbound Without a Clearance?

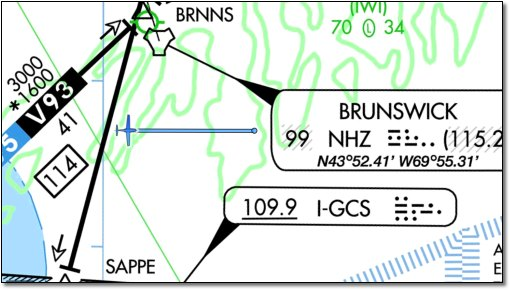

Fly IFR and you’ll run into this situation soon enough: You’re on a base-leg vector to the localizer or inbound course. A kickin’ tailwind has you screaming over the ground. The needle comes alive, and you know you need to start the turn now or you’ll overshoot. However, ATC seems to have forgotten you. Do you start the turn as you try to verify you’re cleared to intercept the inbound course? Or do you hold your heading while clamoring for the clearance, knowing you’ll blow through and need a new heading to re-intercept?

This is one of those places where there’s a right and wrong answer per the regs, but it’s not so cut-and-dry in the real world. By the book it’s simple: You have not been cleared for the approach, so turning off your heading is a violation of 14 CFR 91.123 unless you have good reason to suspect communications failure or it’s an emergency. By the book, you’re going to blow through that inbound course.

Breaking the Rules

In practice, we often exercise a bit more self-determination tempered by situational awareness.

There are really only two possibilities in this situation: One is that the controller got distracted and wants us to turn. The other is the situation has changed, the controller plans to vector us through the inbound course, and has forgotten to tell us that by saying something like, “Fly heading 360. Vectors across the localizer.”

Obviously, the best thing to do is ask, “Do you want us to join the course inbound?” If the frequency is jammed up, you can raise your virtual hand by pushing IDENT to get the controller’s attention. Hopefully, one of those will do the trick.

But it might not. My experience is that if the controller is busy with other aircraft, or if I’m at a remote airport where I know the little blip representing me is in the back 40 of the controller’s scope, they probably want me to start the turn. More often that not, that’s what I’ve done, usually with a call to confirm that was right if it’s a non-towered airport, or even a quick call to Tower requesting that they relay the information.

Maybe I’ve just been lucky, but I’ve never been reprimanded for this. Quite the contrary; I’ve been apologized to and thanked plenty of times.

Could I have gotten in trouble? Sure. This decision carries risk. Aviation is all about managing risk, however, so how does this situation fit in?

Step one is working to avoid the situation altogether. Masterful IFR requires maintaining a pervasive awareness of the situation. You should know you’re converging on the final course with a tailwind, so you can proactively ask ATC if you’re cleared to intercept the final approach course even though you aren’t close.

Suppose you see this situation brewing while still a ways out on the base leg and your moving map makes it clear that your downwind heading is more like a 45 that’s diminishing distance between you and the inbound course rapidly. You could preemptively request the final heading and clearance rather than waiting. “Portland Approach, Cirrus Two Fox Tango. Request heading 220 now and approach clearance.” We’re all people. Sometimes a simple request makes life easier for everyone.

This isn’t for everyone. The consequence of obeying the letter of the law and flying through the localizer is usually only wasted time. I wouldn’t fault anyone for just trucking along and waiting. But tt’s still worth mentally preparing for this situation. If that missed turn inbound puts you on course to rising terrain or other traffic you can see via your avionics, you have a bit more justification for taking matters into your own hands. The last thing you want is for the controller to remember you because a low-altitude or traffic alert went off in the control room.

The Opposite Issue:

Communicating Before Turning

Question for you: When ATC tells you, “… left turn 130,” what’s the first thing you do?

Most people key the mic and parrot back the heading. Personally, I prefer to swing the heading bug and start the turn. I have two reasons.

The primary one is I can see if that turn makes sense to me before I accept it. If a left turn to 130 is a 280-degree turn, maybe ATC meant right, or maybe I misheard 130. Instead of accepting, I can ask for verification when I key up.

The second reason is to prevent spitting back a heading—and then forgetting to actually start the turn because I was in the middle of some other task when it came in. (Not that I’ve, um, ever done that or seen anyone else do it.) Even though ATC is waiting on your response, it only takes 2-3 extra seconds before you reply. Even New York controllers have that much patience. Well, usually.

Tech Question of the Month:

The moving map display in ForeFlight can show a track vector (line) projected in front of the airplane. This length of this line can be configured to show:

A. Time, extending to a point from 15 seconds to 10 minutes ahead

of the airplane

B. Distance, extending to a point 0.5NM to 50 NM ahead of the airplane

C. Either time or distance

D. Both time and distance, however one must be primary (i.e., you can

show 2 minutes and see that at the current speed that’s also 3.64 miles)